Private Thomas Swatton – 66th Regiment of Foot

This story will be one of a series of odd ones in the sense that I have no concrete evidence that the subject is a direct relation but there are a few strong indications that he really couldn’t be anything else. Firstly, my surname is unusual, there being less than 700 people sharing it in the UK, less than a 1000 in the world. Secondly, the name doesn’t come from a profession (like Smith or Cooper) or a physical characteristic (like Short or Brown) which could easily have very discrete origins for people sharing that name; rather it would seem it comes from a village name in Lincolnshire – a single root which, however remotely, we all seem to share. And thirdly, the Thomas Swatton here was born just a few miles down the road from where my own great-great-great grandfather was born… altogether, I’m convinced there must be a familial link.

So why is this Thomas Swatton of interest? Well, anyone who has read any of my articles will have picked up I am very interested in military history and it just so happens that this Thomas joined one of the more interesting regiments at just about the most interesting time in its history and he served through some of the most traumatic experiences any soldier would care to experience.

Thomas’ discharge papers somehow still exist and they reveal quite a story.

A private in the 66th Regiment light company

He enlisted in the 66th Regiment of Foot on 29th Aug 1804 at the age of nineteen. He would go on to serve in the same regiment for 20 years 270 days (the army is very specific when it comes to record keeping).

The early years of his service were spent in relatively uneventful garrison duty in southern Ireland but when the British government decided to send a land force to the continent to oppose the French armies of Napoleon, the 2nd Battalion of the 66th Regiment (2nd/66th) were assigned to the force that embarked for the Peninsular in March 1809, arriving at the mouth of the Tagus on 4th April, disembarking two days later and immediately marching north towards Oporto under the overall command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, not yet titled the Duke of Wellington.

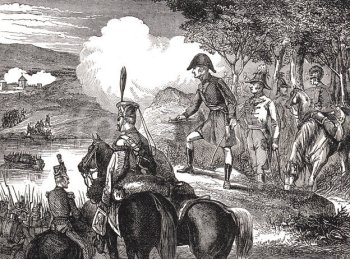

Marshal Soult, commanding the French garrison in Oporto, had the bridges across the River Douro destroyed and mistakenly assumed his force was safe from attack across the wide, fast-flowing river. However, Wellesley pushed across the light companies of the 3rd, 28th and 66th regiments who were brigaded together in a few barges that had been cut out from the far bank. They secured a foothold in a seminary building on the French bank and the rest of the brigade followed across as quickly as they could.

The arrival of fresh troops enabled a portion of the brigade to assume the offensive, and advance against a 7-gun battery, which they carried in the face of a withering fire of grape and musketry.

Crossing the Douro

Shortly after noon, the French evacuated the lower town of Oporto, and the inhabitants rushing down to the now unguarded quays, jumped into boats and rowed across to the south bank.

Sherbrooke’s Brigade of Guards at once went over in these boats; and almost at the same time General Murray, who had crossed the river at a ferry point three miles upstream, was seen advancing down the right bank with the German Brigade and the 14th Light Dragoons.

At this the French broke and abandoned the city. In this action the French lost 500 men and 5 guns, (one of which was taken by the 66th) in the field, besides leaving 50 guns, a quantity of military stores, and all their sick at Oporto. The British casualties numbered 115 killed and wounded; the 6th alone lost 35 men, or nearly one-third of the total.

That same evening, Sir Arthur Wellesley issued the following Order : —

“G.O., Oporto, 12th May, 1809. The Commander of the Forces congratulates the troops upon the success that has attended the operations of the last four days; during which they have traversed above 80 miles of most difficult country, have carried some formidable positions, have beaten the enemy repeatedly, and have ended by forcing the passage of the Douro and defending the position so boldly taken, with a number far inferior to that by which they were attacked.

In the course of this short expedition the Commander of the Forces has had repeated opportunities of witnessing and applauding the gallantry of the officers and men.”

It had certainly been a baptism of fire for the 66th.

More was soon to come…

Two months after the crossing of the Douro at Oporto, the 66th was part of Rowland Hill’s division at the two-day battle of Talavera where the exhausted survivors witnessed the horror of many wounded troops, incapable of moving by themselves, being burned alive when the tinder-dry grassland caught fire towards the end of the battle. And their sacrifice had been for nought as the following day Wellington received intelligence that Marshal Soult was advancing with 30,000 troops to cut his lines of communication and so he was forced to retreat back to the Portuguese border.

After engaging the French again at Bussaco, Wellington then withdrew his forces into the prepared defences of Torres Vedras and it wasn’t until May 1811 that the 66th was involved in another major action, at Albuera, where they were all but annihilated.

The 66th had been assigned to the command of Marshal Beresford, leading a combined British, Portuguese and Spanish force besieging the city of Badajoz. When the French Marshal Soult marched up from Seville, with his Army of Andalusia, to relieve the garrison in Badajoz, Beresford broke off the siege to meet them in battle around the village of Albuera.

The main French attack fell on the Spanish brigades on the flank. In response, Beresford brought up Stewart’s 2nd Division to support the Spanish on their right. The leading brigade, Colborne’s, climbed the hill in the face of a blinding hail storm and went into action as each battalion reached the crest, only to be caught still deployed in line by the French light cavalry, the lancers of the Polish Vistula Legion and a regiment of hussars.

Massacre at Albuera

Three battalions of Colborne’s brigade, including 2nd / 66th Foot were virtually annihilated in just a few minutes as the French cavalry broke through them.

At this point in the battle, Soult failed to act to secure the victory by vigorous use of his overwhelming strength in cavalry and Beresford was given the opportunity to reform his line. The brigades of the 4th Division were brought up to relieve the Spanish and held the French back under a storm of artillery fire and musketry. In a twenty-minute exchange of fire these battalions were reduced to ruin but they held their ground.

When the Fusilier Brigade ascended the ridge and attacked the French with the Portuguese battalions of the 4th Division and Abercromby’s Brigade, Soult realised he had lost the initiative, abandoned his attack and withdrew.

After the battle, Wellington acknowledged that another such “victory” would ruin his army and Marshal Soult wrote: “There is no beating these troops… I had turned their right, pierced their centre and everywhere victory was mine – but they did not know how to run!”

And what of Thomas’ unit? The 66th had 16 officers and 310 men killed, wounded, and missing in the devastating attack by French cavalry. The battalion went into action 400 strong, and the following day only 53 bayonets mustered at parade.

If Thomas was one of the wounded we will never know but we know he survived to fight on, and much more fighting was yet to come.

Following the massacre at Albuera the 66th Foot struggled to replace its losses from its depot back in England and opinion was divided on what to do with seriously under-strength battalions as Sir Charles Oman wrote in his history of the war:

“What was to be done if a Peninsular battalion had got very low in numbers …and had few or no recruits at its British depot ready to be sent out? This was the case in December 1812 with twelve good old battalions of the Peninsular Army. The Duke of York maintained that since they all showed under 350 effectives…they must come home at once. But Wellington had other views. He held that a well-tried battalion acclimatised to Peninsular service was such a precious thing…that it would be best to combine the wasted units in pairs as ‘Provisional battalions’ of 600 to 700 bayonets.”

Thus was the situation with the 2nd / 66th Foot in June 1813 as Wellington faced up to Joseph Bonaparte at the Battle of Vitoria in northern Spain. They were combined with the 2nd / 31st Foot to create the 1st Provisional Battalion.

Vitoria

Vitoria was to be the largest battle of Wellington’s career to date, he having 80,000 troops at his disposal which he used to devastating effect, completely routing the French and capturing all but one of their 150 guns. The aftermath of the battle was notorious for the looting which took place of Joseph Bonaparte’s baggage train full of the loot he has brought out of Madrid when he abandoned the capital. There being no evidence of any great wealth coming into the family I’m guessing that Thomas missed out on any rich pickings!

However, the victory at Vitoria opened the way for Wellington to cross the Pyrenees and invade France which he duly did.

As part of Wellington’s victorious army, the 66th pursued the French Army into France and fought at the Battle of the Pyrenees in July 1813, the Battle of Nivelle in November 1813 and the Battle of Nive in December 1813 as well as the Battle of Orthez in February 1814 and finally the Battle of Toulouse in April 1814, the last battle fought by the British before Napoleon abdicated.

When Napoleon escaped from Elba in the spring of 1815 and the 100 days campaign began which culminated in his final defeat at Waterloo, the 66th Foot played no part.

However, their experience of Napoleon was not quite over.

In 1816 the 2nd / 66th sailed for St Helena to guard Napoleon, who had been sent there in exile following his defeat at Waterloo. For five long years the regiment was posted there guarding the emperor. In the well-known engraving of Napoleon staring forlornly out to sea there is a sentry standing guard in the background… just maybe that would be Thomas!

In 1816 the 2nd / 66th sailed for St Helena to guard Napoleon, who had been sent there in exile following his defeat at Waterloo. For five long years the regiment was posted there guarding the emperor. In the well-known engraving of Napoleon staring forlornly out to sea there is a sentry standing guard in the background… just maybe that would be Thomas!

When Napoleon died in 1821 the whole regiment formally paraded past his coffin as a mark of respect. Finally, it was grenadiers of the 20th and 66th Regiments who bore the emperor’s body to the grave.

At last, the 66th could return home.

The final few years of Thomas’ service were uneventful and after almost 21 years of service he was honourably discharged, described as being “worn out from service in the Peninsular and St. Helena”. I think the poor bugger had done enough.